High summer in Stratford-upon-Avon and at the RST the season is in full swing. Three Shakespeare productions are running in the main theatre, and on Thursday it was possible to see two plays back to back. In the afternoon there was All’s Well That Ends Well, followed in the evening by Shakespeare’s longest and most famous play, Hamlet. Audiences have been able to see the Countess of Rossillion (Charlotte Cornwell) and the King of France (Greg Hicks) turn into Gertrude and Claudius, and even more interestingly Bertram (Alex Waldmann) and Parolles (Jonathan Slinger) become Horatio and Hamlet.

Performing this double act is a reminder of why the RSC has become such a great and famous company over its fifty year history. It can only be achieved by playing long seasons, with a cross-cast company of experienced professionals. I’m sure there will have been some hardy souls in the audience who managed the double – I’m afraid I wasn’t among them, but I’ve seen both plays separately.

Of the two, I much preferred the All’s Well That Ends Well, directed by Nancy Meckler. David Farr’s Hamlet seemed to me to be a production that was trying too hard to be clever, with a concept that interfered with the play rather than clarifying it. Though as I saw Hamlet early in its run there is now a sneaking suspicion in my mind that, now the company has been together longer, I would enjoy that production more too.

Meckler’s production is entertaining and clear, not always the case with this notoriously difficult play. This link leads to reviews and interviews with Charlotte Cornwell and Alex Waldmann. It could be suggested that the characters are a bit too likeable. There aren’t any villains here. Some productions make Parolles deeply unpleasant, but in this production we can’t help sympathising with his weakness at the same time as we disapprove of his behaviour. It’s the same with other characters: Helena is humble and passionately in love, where she can sometimes be a bit of a prig, annoyingly always in the right. And Bertram is sometimes played as such a flawed character that we wonder why Helena is so keen to spend her life with him. Meckler and her company bring off the difficult feat of making us aware of the faults in all of us, allowing us to forgive them (and ourselves) at the end.

It reminded me of that exchange in Julius Caesar, where Brutus and Cassius argue. Brutus frankly declares “I do not like your faults”. Cassius responds “A friendly eye could never see such faults”. Brutus retorts “A flatterer’s would not, though they do appear / As huge as high Olympus”. We accept our friends, warts and all, rather than being blind to their faults, and it’s much the same with the characters in this production.

Alex Waldmann’s Bertram is young and easily led, rather than bad. He’s on Helena’s side during the scene where she chooses a husband, gives her the thumbs up, until he realises she has set her sights on him In the final scene, trying to lie his way out of the accusations against him his despairing look to the audience acknowledges that he knows he’s got to change.

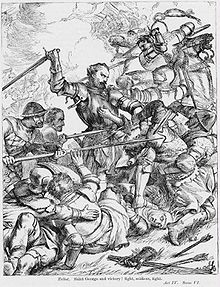

I loved the use of music and dance in the production, quickly explaining elements of the plot as in the opening, where Bertram’s partying is halted by the letter telling him of his father’s death. When Bertram childishly runs away to war instead of facing his responsibilities he stands centre stage, an Action Man doll being dressed up as a soldier. And the battle in which he distinguishes himself is an elaborately choreographed ritual combat. War may be a theme of the play, but here it seems to be a way of escaping the reality of growing up.

Elsewhere dance is a celebration of life. The King of France is transformed by Helena’s remedy, showing off his complete recovery by partnering her in a dance before doing a spot of break-dancing, a cartwheel and a handstand.

The Countess is always at the centre of the play, and Charlotte Cornwell plays her as a loving but troubled mother. There’s a section on Designing the Countess on the RSC website in which the designer talks about the decisions made about how to dress her, but I’m surprised that in a production that emphasises the active roles women take to support each other she appears so conventional, and made to appear unnecessarily old: the widow, for instance, is much younger.

At the end of the play she remains a figure in mourning black. The costume exhibition Into the Wild, currently being shown at the RSC, shows that it’s always the same. It includes costumes for three Countesses from the past: Peggy Ashcroft’s from 1981, Judi Dench’s from 2003, and Edith Evans’ from 1959. Each wears a long black dress, and each actress’s hair was worn in a grey bun. I’d love to have seen Charlotte Cornwell (the best Rosalind I’ve ever seen, back in 1978), ditch the grey wig, the long black dress and the pearl necklace, and indulge in a life-affirming dance of her own to close the play, when all really does end well.

RSC production photographs copyright RSC, taken by Ellie Kurttz