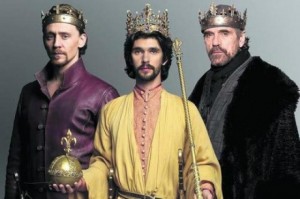

Among the must-see television shows for Shakespeare fans this summer has been Simon Schama’s Shakespeare. Love him or hate him, he’s the UK’s highest-profile historian. His style is individual, even eccentric, one minute generalising about the broad sweep of history, the next focusing in on some carefully-chosen detail. His two part series on Shakespeare has inevitably concentrated on Shakespeare’s view of history, and on how important it is to understand Shakespeare’s place in it for an understanding of his plays. The first one concentrated on the history plays themselves, the second, which I thought the better of the two, looked at the great tragedies, especially King Lear where the role of the monarch is most shatteringly explored.

The second documentary is on IPlayer only until early evening on 6 July, but with any luck they will be repeated.

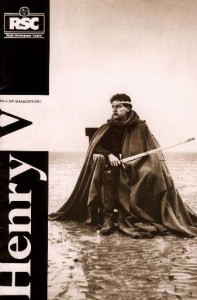

Schama hasn’t tangled much with Shakespeare’s comedy, confining himself to profiling that great character, Falstaff. On Saturday the BBC also began The Hollow Crown cycle of Richard II, Henry IV Parts 1 and 2 and Henry V, so we’re about to meet Simon Russell Beale’s Falstaff this weekend. Later this summer Beale is performing that rarity, Timon of Athens, at the National Theatre. In the first of Schama’s programmes we saw and heard Roger Allam, a great Falstaff at the Globe a couple of years ago, memorably delivering Falstaff’s debate with himself about Honour while walking around a graveyard. “What is Honour? A word…What is that honour? Air…Who hath it? He that died a’ Wednesday”. For anyone who finds Shakespeare’s verbal flourishes a bit much, this spare speech shows that Shakespeare can say it all in just a few syllables when he wants to.

I was less sure about Schama sitting at a table with Harriet Walter reading a scene including Doll Tearsheet, but I can’t blame him for wanting to have a go. He used some of the greatest interpreters of Shakespeare on stage, and The Hollow Crown brings together more of them. In Richard II we had Patrick Stewart as John of Gaunt, and David Suchet as the Duke of York, two distinguished Shakespeare veterans. If you’ve only ever seen David Suchet as Poirot, you don’t know what you’ve missed. I still remember him in the RSC’s 1980 Richard II, playing Bolingbroke. I’ve never heard anyone deliver his lines about absence and loss better:

O, who can hold a fire in his hand

By thinking on the frosty Caucasus?

Or cloy the hungry edge of appetite

By bare imagination of a feast?

In Richard II you could almost have missed another accomplished performer of Shakespeare in the tiny role of the Gardener. David Bradley’s better known these days as the caretaker, Filch, in the Harry Potter films, but he too has great Shakespeare credentials, mostly playing character roles. He was the funniest Andrew Aguecheek I’ve ever seen in the RSC’s 1987 production of Twelfth Night in which, as it happens, Roger Allam played that great warm-up for Falstaff, Sir Toby Belch and Harriet Walter played Viola. The comic partnership of Allam and Bradley almost overshadowed the real comic heart of the play, Malvolio, played by Tony Sher. Quite a cast.

But the most extraordinary role I’ve seen him play was in 1990 when he was the Fool in the National Theatre’s touring production of King Lear with Brian Cox as the king (the picture does not do these performances justice). As Schama pointed out, James I had a fool at court allowed to say what others were not, but the Fool in King Lear criticises the King very sharply. In inexperienced hands Shakespeare’s fool can seem incomprehensible, but Bradley knew exactly what he was saying. We first see the Fool when Lear’s already suffering the consequences of his actions, and calls for his “pretty knave”, hoping for some comfort. Instead, Bradley’s Fool reminded him, over and over again, of his stupidity.

“Dost thou call me fool, boy?”, Lear asks. The fool replies “All thy other titles thou hast given away; that thou wast born with”. A few lines later “Thou hadst little wit in thy bald crown when thou gav’st thy golden one away” and later again “I had rather be any kind o’ thing but a fool, and yet I would not be thee, nuncle”. It’s a bitter and devastating exchange from someone who has no power except the power to entertain with words.

Schama drew the parallel between the role of the licensed fool and the role of the King’s Men and its resident playwright. With no power, but relative freedom to speak, they were given the chance to indirectly point out the folly of the king’s actions. In King Lear the fool is threatened with the whip, and certainly playing companies could go too far. But Shakespeare seems to have managed to stay on the right side, perhaps because Lear is redeemed by the end of the play.

The current BBC season stresses Shakespeare’s ability to comment on current events and shows that he wasn’t then, and isn’t now, just an entertainer.

If you want to catch it again, Richard II is available until 28 July here on IPlayer.