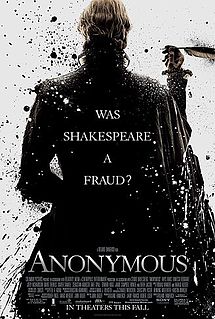

After experiencing Hollywood’s wildly inaccurate version of history in the film Anonymous I’ve returned with relief to a book which looks at the reality. Dr Robert Bearman has continued the task, begun in the 1920s, of transcribing and editing the main documents detailing the history of Stratford-upon-Avon in Shakespeare’s lifetime. His book Minutes and Accounts of the Stratford-upon-Avon Corporation Volume VI: 1599-1609 has just been published by the Dugdale Society.

After experiencing Hollywood’s wildly inaccurate version of history in the film Anonymous I’ve returned with relief to a book which looks at the reality. Dr Robert Bearman has continued the task, begun in the 1920s, of transcribing and editing the main documents detailing the history of Stratford-upon-Avon in Shakespeare’s lifetime. His book Minutes and Accounts of the Stratford-upon-Avon Corporation Volume VI: 1599-1609 has just been published by the Dugdale Society.

Records of the activities of the Corporation were kept from its foundation in 1553. These are still in existence at the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive and continue to demonstrate what life was like in the town in Shakespeare’s lifetime. Shakespeare’s father John was an active Member of the Corporation in earlier years, and during the period covered by the book Members included people who knew Shakespeare, like Francis Collins the lawyer and Hamnet Sadler, both witnesses to Shakespeare’s will, and there are many mentions of families like the Quineys.

The detail is fascinating. Petty and not so petty crime, including murder, building improvements, the state of the roads, rubbish disposal, are all subjects that still preoccupy us in our towns and cities. Other records remind us how much the world has changed. Dr Bearman tells us:

“We read of complaints that the high bailiff, no less, had his head ‘grievously broken’ whilst trying to put a stop to a brawl in a local tavern…. of the arrest for trespass of the bailiff, chief alderman and four other aldermen after they had symbolically broken into the Bancroft, illegally enclosed by the lord of the manor, [doing damage] to the value of forty shillings; and of the excommunication and expulsion of the of the vicar, Richard Byfield for being too much of a Puritan for his own good”

Neither Shakespeare, then at the height of his success in London, nor his immediate family, feature very much in these records, but that’s only to be expected as affluent landowners rarely get into trouble with the law. There are, though, echoes. As Bearman notes, the behaviour of the officers of the Stratford watch, the equivalent of local policemen, reminds us of the self-important Dogberry and his men in Much Ado About Nothing. In 1608 it’s reported that ‘the constables are very negligent in their return and charging of sufficient watchmen and that those watchmen which are ordinarily charged neither begin the watch at a lawful hour, and always for the most part break off and depart before the lawful hour’. In Shakespeare’s play the watch, supposedly “good men and true” discuss their evening duties to apprehend vagrants, drunkards and thieves. “You are to call at all the ale-houses, and bid those that are drunk get them to bed”, while making it clear that they will not intervene should they encounter trouble. The watchmen themselves expect a quiet night:“Let us go sit here upon the church-bench till two, and then all to bed”. Another Shakespeare play, Measure for Measure, also features a constable, Elbow, who makes a joke of his name: “I do lean upon justice, sir”.

I particularly like the section in the book dealing with the 1606 casting of a new bell for the Guild Chapel. The accounts list what had to be purchased: the metal for the bell, stone for the furnace, bags of coals to dry the moulds, nails, timber for the bell frame. Then there are the payments to people: Richard Dawkes who cast the bell, Spenser and others “for helpinge us out of the pit with the bell and for gettinge her into the chapel in money and drinke”, and to “Richard Greene and Harrington for watchinge the night after the bell was caste”. The bell cost in total £28 7s 1d, a significant proportion of the Corporation’s expenses. Although it’s unlikely that Shakespeare was in Stratford when it was being made, he would have heard the bell striking from, New Place, just across the road.

We shouldn’t forget Mairi Macdonald who has made access to the documents immeasurably easier by creating the name index to all six volumes in the series, and including it in this one.

During this period Stratford found itself at the heart of events of national importance. Clopton House, just outside Stratford, was occupied by one of the conspirators in the Gunpowder Plot. I’ll be writing a blog about what the book shows to have happened around the anniversary of the plot, 5th November.

If you’re interested in acquiring a copy of this excellent book, please contact the secretary, Cathy Millwood, at dugdale-society@hotmail.co.uk . Readers of this blog will be able to acquire it at the bargain rate of £30, a discount of £5 off the normal price.