I’d never heard of the little village of Tong and its church until recently when some visiting relatives mentioned its Shakespeare connections. So I paid a visit to this tiny village in Shropshire to find out more.

The church is sometimes called the “village Westminster Abbey” because of the large number of magnificent tombs it contains, mostly for the Vernon and Stanley families. The name Stanley will ring a bell with you if you know Richard III. Towards the end of the play Stanley, who wants to fight for Richmond against King Richard, is forced to remain neutral in the run-up to the battle of Bosworth because the king has taken Stanley’s son George hostage and threatens to kill him. Young George is Richard III’s last potential victim. After the death of Richard during the battle, Richmond is proclaimed King Henry VII.

As usual, Shakespeare is pretty casual about historical details. “Young George” was actually quite mature, and the Stanley in the play is a conflation of two members of the family. Stanley is referred to as Earl of Derby before he was granted this honour. The key elements of this story, though, are taken accurately from the play’s sources, Sir Thomas More’s Life of Richard III and the Chronicles of Halle and Holinshed.

Stanley did delay as long as he could before coming in on Richmond’s side, and after the battle George is released unharmed. The new King Henry VII rewarded Stanley for his loyalty by creating him 1st Earl of Derby in 1485.

The magnificent tombs in Tong Church are not, though, of the Earls of Derby, but less prominent members of the family. They are so tightly packed it’s difficult to get clear photographs, especially of the impressive double-decker Stanley monument erected to Sir Thomas Stanley and his wife Margaret Vernon and their son Sir Edward Stanley (1562-1632). Sir Thomas (died 1576) was the second son of the third Earl of Derby. At each end of the upper tomb are lines of poetry.

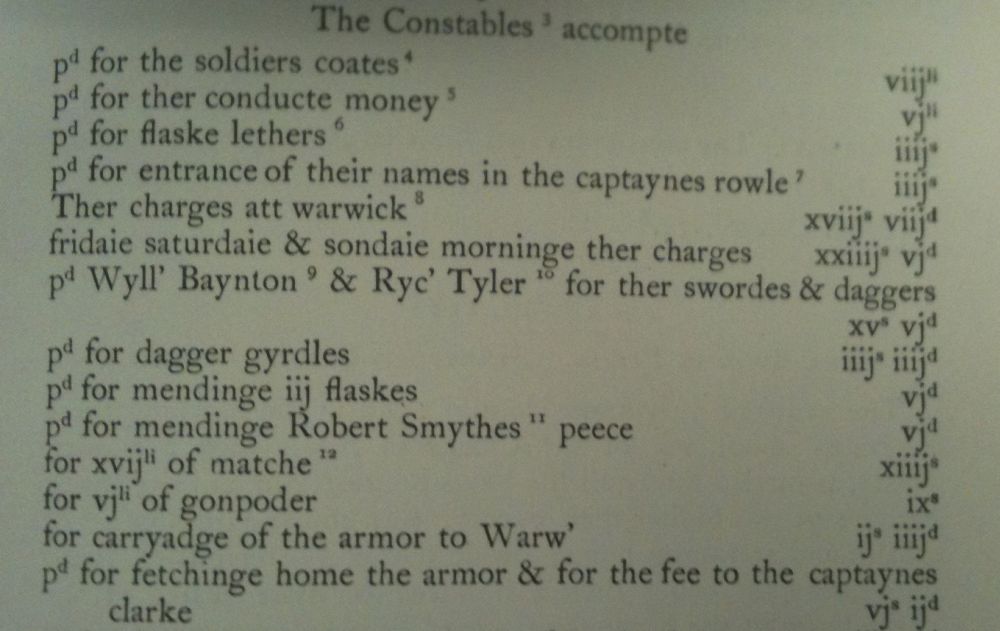

Ask who lyes heare but do not weep,

He is not dead he dooth but sleep

This stoney register, is for his bones

His fame is more perpetual than theise stones

And his own goodness with himself being gon

Shall lyve when earthlie monument is none

On the other end of the tomb:

Not monumental stone preserve our fame,

Nor sky aspiring pyramids our name

The memory of him for whom this stands

Shall outlive marbl, and defacers hands

When all to tymes consumption shall be geaven

Standly for whom this stands shall stand in Heaven.

It’s rumoured that these lines were written by Shakespeare for this tomb, and there are links between Shakespeare and the Stanley family. The strongest comes about because Ferdinando, Lord Strange, had his own company of players who performed some of Shakespeare’s plays. One copy of the book Plutarch’s Lives of the noble Grecians and Romans, published in 1579, now owned by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, has a fascinating history. On publication it was given to Henry Stanley, 4th Earl of Derby and from him it passed to his son Ferdinando, 5th Earl of Derby, who died in 1594. Shakespeare based his Roman plays, including Antony and Cleopatra and Julius Caesar, on the stories in this book, and because Ferdinando and Shakespeare knew each other there is a strong possibility that this could be the copy he used.

There is a signature in the book indicating that in 1611 it became the property of Edward Stanley, probably the man whose effigy is on the lower deck of the monument and a real Shakespeare connection.

But did Shakespeare write the epitaph? Shakespeare might have written the words on his own grave, and there’s an old tradition that he wrote an epitaph for a Stratford neighbour, John Combe, so it seems possible. The story is made more complicated because the exact date of the tomb is unknown, though there is apparently a reference to the poem in a document dated 1620. Sir Thomas Stanley died when Shakespeare was only 12, so if Shakespeare wrote them to him they can only have been written years later, and Sir Edward Stanley died 16 years after Shakespeare’s death.

As so often with anything relating to Shakespeare, the rumours far outnumber the certainties, and the monuments in Tong Church remain a magnificent mystery.