It’s been an exciting few days for anyone interested in manuscript versions of literary works. At Sotheby’s on 14 July a large number of magnificent manuscripts written by some of the most famous names of English literature was auctioned. Items by Lord Byron, Andrew Marvell and Charlotte Bronte were outshone by the working draft of Jane Austen’s unfinished novel The Watsons which sold for slightly under a million pounds.

This manuscript is the only surviving original draft of a novel by Austen, and has been in the care of Queen Mary College, University of London. It’s already been digitised as part of a project entitled Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts which offers both digital images and a transcript of the remaining pages in her own hand, and offers the ability to search for words or phrases contained in them.

By the end of the day it was revealed that the purchaser of the manuscript was the Bodleian Library, Oxford where it will be put on display later this year. The fact that it is already available online won’t diminish enthusiasm to see and study the original, as “The manuscript provides a glimpse into the mind of Austen as every page is littered with crossings out, revisions and additional text”.

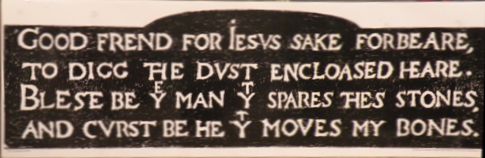

It’s a matter of enormous regret that we have so little in Shakespeare’s hand. Not a single literary manuscript, except for the disputed pages from the play Sir Thomas More owned by the British Library, and only a few signatures on legal documents from which it’s not possible to infer anything about the man himself.

With none of the magical manuscripts themselves, the comments that people made about Shakespeare’s writing habits take on special interest. They indicate that Shakespeare wrote speedily, pausing to make few revisions.

In their essay “To the great variety of readers” in Shakespeare’s First Folio, John Heminges and Henry Condell wrote “His mind and hand went together, and what he thought he uttered with that easiness that we have scarce received from him a blot in his papers”.

Ben Jonson, in Timber, or Discoveries was less sure this was a virtue:

I remember, the Players have often mentioned it as an honour to Shakespeare, that in his writing, (whatsoever he penn’d) hee never blotted out a line. My answer hath beene, would he had blotted a thousand….He…had an excellent Phantasie; brave notions, and gentle expressions: wherein hee flow’d with that facility, that sometime it was necessary he should be stop’d.

There’s much to be learned about famous writers by the study of their manuscripts, and currently a series of electronic projects are helping this understanding.

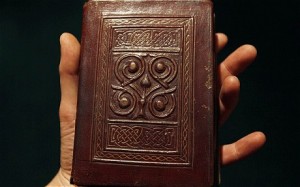

On the same day as the Sotheby’s sale the British Library announced its aim to acquire the earliest surviving European book, the St Cuthbert’s Gospel. The British Library’s Medieval and Earlier Manuscripts Blog is a wonderful source of images of ancient manuscripts, which include some secular works such as a fourteenth century manuscript of the poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and another poem entitled Pearl, from the collection of the antiquarian Sir Robert Cotton who died in 1631.

At the end of July a conference is being held in London to launch the Catalogue of English Literary Manuscripts 1450-1700, an online record of surviving manuscript sources for over 200 authors of the Early Modern period.

All these projects aim to celebrate the actual document, such a powerful factor in the purchase of the Austen manuscript. Earlier in 2011 the LitHouses group of museums, libraries and archives representing some of the most important literary figures in the UK held a specialist conference at Dove Cottage in Grasmere, addressing issues regarding the interpretation and display of original literary manuscripts.