On the whole, Shakespeare kept out of trouble. He got his girlfriend pregnant, and didn’t always pay his taxes, but compared with the violence of the lives of his contemporaries Marlowe, Kyd and Jonson, his was uneventful and that was probably the way he liked it. He could get all the drama he needed within his own imagination.

There is though one document that seems to suggest that Shakespeare might have been involved in some seriously unlawful activity. On 29 November 1596 a writ of attachment was issued to four people, including Shakespeare, in Southwark. It’s in Latin, and the translation reads:

Be it known that William Wayte craves sureties of the peace against William Shakspere, Francis Langley, Dorothy Soer wife of John Soer, and Anne Lee, for fear of death, and so forth. Writ of attachment issued by the sheriff of Surrey, returnable on the eighteenth of St Martin.

This account appears on the National Archives site.

Writs of attachment were a way of keeping the peace. As Schoenbaum reports in his Documentary Life, “the complainant swore before the Judge of Queen’s Bench that he stood in danger of death, or bodily hurt, from a certain party. The magistrate then commanded the sheriff of the appropriate county to produce the accused person or persons, who had to post bond to keep the peace”.

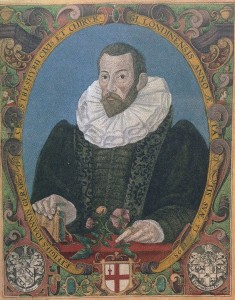

Some time earlier, Francis Langley (1548-1602) had taken out a writ against William Gardiner (1531-1597) and William Wayte (1555-1603), making similar claims against them. These documents were found by Leslie Hotson who wrote about them in his 1931 book Shakespeare versus Shallow. It appears that the document mentioning Shakespeare was issued in retaliation for the first. Hotson also noted that even earlier William Gardiner, a Justice of the Peace for Surrey with a reputation for corruption, had accused Langley of perjury, though the case was dropped. William Wayte was Gardiner’s stepson who was described as “a certain loose person of no reckoning or value” who worked as an agent for his powerful stepfather.

The bare facts of the case require some kind of interpretation, and many authors have suggested what might have been behind them. In The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare, Stanley Wells focuses on Leslie Hotson’s findings, including the fact that Gardiner cheated Wayte out of his inheritance, and in which he “proposes that in The Merry Wives of Windsor Shakespeare satirises Gardiner as Shallow and Wayte as Slender.”

In 2011 Mike Dash, in a colourful piece entitled “William Shakespeare, gangster”, suggested that the document shows Shakespeare to have been a “dangerous thug”, “heavily involved in organized crime”. For Dash, the women are clearly prostitutes and the whole story is “a squalid tale of gangland rivalries in the theatrical underworld”.

Dash clearly needs to calm down, but even more measured modern accounts suggest that Wayte was attacked in the street. In 1596 Shakespeare was 32, Langley was 48 and the other two named were women, at least one of whom was respectably married. For years nothing was known about Dorothy Soer and Anne Lee but this post suggests who they may have been.

It hardly sounds like a Romeo and Juliet-style street fight in which Wayte’s life was seriously in danger. David Fallow also considered the case in a post for Blogging Shakespeare in 2012.

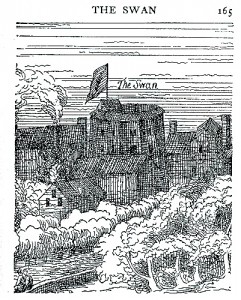

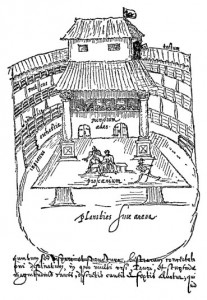

So if Wayte was not set upon by a dangerous gang, what was it all about? By looking back through the records Schoenbaum found that Gardiner and Langley had a long-running feud. Gardiner had made many enemies through his underhand financial dealings and was both wealthy and powerful. Langley was responsible for the building of the Swan theatre on Bankside around 1595-6, and documents reveal that Gardiner, having quarrelled with Langley, wanted to close it down. It was let to Pembroke’s Men in February 1597 but had already been used as a playhouse. Perhaps Shakespeare’s company had been playing there at the time Gardiner threatened to pull the theatre down, and this was how Shakespeare had got involved?

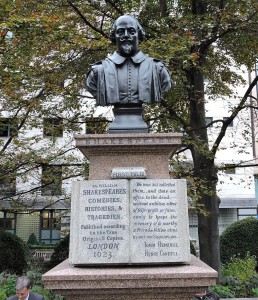

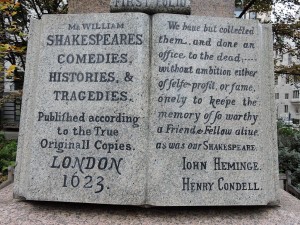

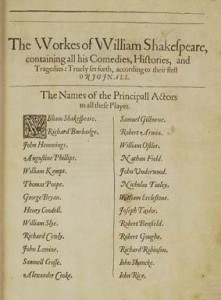

Langley was a none-too scrupulous goldsmith by profession, and in later life was involved in many lawsuits. After 1596 Shakespeare and the Lord Chamberlain’s Men seem to have had nothing to do with him. Shakespeare had a lot to lose in terms of reputation: by 1596 his company had performed before the Queen during Christmas festivities. The respectable John Heminges was now a member of the company. Shakespeare was writing his Henry IV plays. The attempt to acquire the indoors Blackfriars theatre had only recently failed: this would have attracted a more affluent clientele than the outdoor theatres like Langley’s Swan. Just a few weeks before, the College of Arms had drawn up two drafts for Shakespeare’s coat of arms, a move towards further respectability, which Shakespeare seems always to have craved.

Shakespeare’s reputation did not suffer because of this strange episode, his company back performing before the Queen and court just a few weeks later. It’s not such a good story, but the truth of it is that he was probably accidentally drawn into the feud between two other men. In 1596 what Shakespeare was doing was creating the works that were to establish him as a playwright of real substance.

![william-shakespeare-portrait[1]](https://theshakespeareblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/william-shakespeare-portrait1-300x300.jpg)