Passing the jewellery shop at the top of Sheep Street in Stratford-upon-Avon, I’ve often wondered about the statue of a young man who looks across the road towards the Town Hall. I had always assumed it must have a Shakespeare connection because pretty well every statue in Stratford does. On the wall of the Town Hall is the 1769 statue of Shakespeare, and on another corner is the Old Bank with its terracotta sculptures of scenes from Shakespeare’s plays and a mosaic based on the church bust.

A few weeks ago I took a better look. The young man in the statue stands behind a shield bearing the Stratford coat of arms. He wears a cloak, tunic, trousers and sandals that could be from almost any period. His expression is unbearably sad, and his clothes are tattered, but there is something noble, even heroic, about his pose. Both the building and the statue are unmistakeably 1960s, but there is no plaque to say what the statue represents or who it is by. Who is he, and why is it so anonymous?

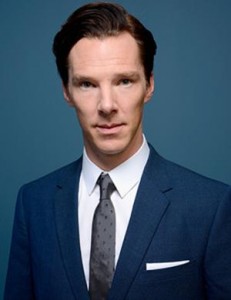

While I can’t say I’ve solved all the mysteries, I now know the statue is called Everyman, the work of the artist Fred J Kormis. I found a great deal of information on the Public Monuments and Sculpture Association website.

Fred J Kormis was born in Frankfurt of Jewish parents in 1887 and died in 1986 in London. As a young man he was apprenticed in a sculptor’s workshop, then at the start of World War 1 he served in the Austro-Hungarian army, but was captured and spent from 1915 to 1920 in a Siberian war camp. After his release he returned to Frankfurt but when the Nazis came to power he was unable to work and fled to Holland in 1933, then England in 1934 where he anglicised his name from Fritz to Fred. He established his own studio in London but this was destroyed by bombing in 1940.

After the war he became well-known for his bronze medals, with a wide range of subjects including the Duke of Edinburgh, the sculptor Henry Moore, Charlie Chaplin and Winston Churchill. The impact of his experiences as a young man in Siberia and Germany can be seen in his more serious work such as The Marchers, another wall-sculpture at King’s College on the Strand in London. For many years he planned a Memorial to Prisoners of War and Concentration Camp Victims and by 1967 the work was well advanced. He hoped to install his series of five figures into a building that had been bombed in World War 2, but no suitable site was found and it was placed in Gladstone Park in the London Borough of Brent in 1969. The figures illustrated aspects of his own experience of imprisonment.

In 2013 West Hampstead Life reproduced an interview with him from the time:

“First there is the numb shock of realizing you are a prisoner in the hands of the enemy. Then there is the dawning awareness of your predicament and the primitive conditions. The next phase is the thought of escape and freedom. After that many succumb to despair and a sense of hopelessness. Others overcome their dejection and manage to escape.”

Kormis had two designs in mind for the fifth and central figure – a figure with outstretched arms, alive and hopeful for the future, or a seated woman, face in hands, sunk in deep grief. “I prefer this but I must admit it is a very sad study. It could be too depressing.”

From 1944 to his death Kormis lived at 3B Greville Place in north London. The house had been home to Frank Dicksee, a Victorian artist who painted many Shakespeare subjects, most famously Romeo and Juliet. The house was later split into flats, and a Stratford link emerges. His neighbour at 3A was the artist and engraver John Hutton, who created the wall of glass angels in Coventry Cathedral and the glass engravings of Shakespeare characters commissioned for the 1964 Shakespeare Centre in Henley Street. Kormis’s Stratford statue was also put in place in 1964, just at the time when he was making plans for his own tribute to those affected by war.

So maybe there is a Shakespeare connection. The Sheep Street statue has always made me think of the boy in Henry V: a young and unwilling participant in war, to whom Shakespeare gives an individual voice, complaining about those he serves; “As young as I am, I have observed these three swaggerers. I am boy to them all three, but…indeed three such antics do not amount to a man….They would have me as familiar with men’s pockets as their gloves or their handkerchiefs, which makes much against my manhood…. Their villainy goes against my weak stomach”. Although it was the most famous of victories, Shakespeare reports that the boys attached to the English army were all killed during the battle of Agincourt.

The statue makes sense when seen in the context of Fred J Kormis’s other work and his preoccupation with the effects of war on individuals. Everyman surely represents all the young men, from Stratford and every other town, sent to war either never to return, or bearing emotional and physical scars.

PS The owl at the foot of the statue is not a symbol of Athena, or the occult. I believe it is intended to deter pigeons. It is totally ineffective.