Unlikely as it seems given the weather, people have been performing outdoors in Britain for hundreds of years, well before the building of purpose-built theatres in Elizabethan London. The medieval mystery cycles were performed in many towns and cities on mobile wagons. Performed annually, the York mystery cycle can this year can be seen in the grounds of St Mary’s Abbey until 27 August. Every few years they revive the popular authentic tradition of taking to the streets performing on mobile wagons.

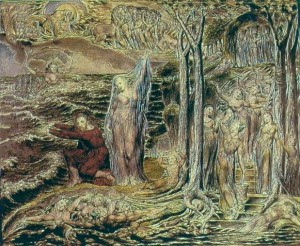

During Shakespeare’s day performances of secular plays took place in many outdoor locations from inn-yards to roughly circular auditoria like the Globe and the Rose. But there’s a long tradition of more informal outdoor performances. These days outdoor productions are more popular than ever. One of the most famous venues is the Delacorte Theatre in New York’s Central Park which has been operating since 1962, though this year no Shakespeare is being produced. In the UK it hasn’t been a bad summer for outdoor Shakespeare in spite of an awful start. If you want to catch some outdoor Shakespeare you’ve still got time as several productions are still running over coming the Bank Holiday weekend. A few of them are free or included in the price of admission, but always check the websites for details.

- The Oddsocks Company is performing Julius Caesar at Athelhampton House and Gardens in Dorset on 24 August and still has a couple of performances in September.

- The Festival Players are performing Richard III at Woodchester Mansion, Gloucestershire on 24 August, at The Jewry Wall Museum in Leicester on 25 August and at Oakham Castle, Rutland on 26 August.

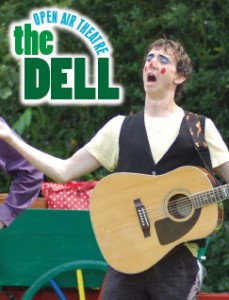

- In Stratford-upon-Avon Cymbeline‘s being performed on 25th, and both Perdita and Florizel and Henry IV Part 1 on 26th,at the RSC’s outdoor performance space, the Dell.

- Also in Stratford there are several performances at Hall’s Croft this week: Romeo and Juliet on 25th, Shakespeare’s Queens on 26th and The Tempest on 27th.

- In London, A Midsummer Night’s Dream is still playing at Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre, but not over the Bank Holiday weekend.

- Shakespeare’s Globe has a full repertoire with Henry V, The Taming of the Shrew, and Richard III, and their touring productions of As You Like It is being performed over the weekend at Tutbury Castle, Burton-on-Trent and of Hamlet at St Donat’s Arts Centre, Vale of Glamorgan.

If you need convincing about how much fun outdoor Shakespeare can be, take a look at this video about Green Stage, who perform Shakespeare in the park in Seattle, Washington.

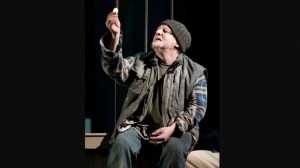

While on the subject of catching things before they’re over, lovers of Shakespeare on stage should taken in an exhibition called Jubilee: Dressing the Monarchy on Stage and Screen at Bath’s Assembly Rooms. It includes the Richard III costume worn by Sir Antony Sher in 1984 as well as costumes worn by Dame Helen Mirren, Dame Peggy Ashcroft and Richard Burton CBE at Stratford, and costumes from recent films on the monarchy such as The Queen and The King’s Speech. I’m sure I’m not the only one to have missed hearing about this exhibition which is only on until 2nd September.