Many traditions and myths relating to Shakespeare have built up in the almost four centuries since his death. As part of the celebrations for Shakespeare’s birthday this year the tradition of placing a new quill pen in the hand of the Shakespeare monument in Holy Trinity Church was revived. The honour of replacing the quill went to the Head Boy of Shakespeare’s Schoool. It was a tradition that many people had heard of, but when did it start, and why did it ever stop?

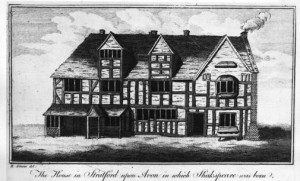

The archivist at King Edward’s, Shakespeare’s School, knew that the Captain of School had replaced the quill in 1893 at the time when the school began processing down to the church to celebrate the birthday. A local historian remembered an attempt to revive the tradition in the 1960s by the then vicar. But the fullest account I’ve found is in Val Horsler’s book Shakespeare’s Church. She remarks that the tradition began in 1861 when the monument was cleaned and repaired. The original stone quill had been stolen, and replaced, numerous times, and the monument had been damaged by “sacrilegious visitors and senseless nonentities” scratching their names in the stone and chipping off fragments of it. The damage could have been worse: the monument is above head height on the wall, beyond the reach of most who were accustomed to taking home souvenirs from other sites like Shakespeare’s Birthplace.

The author suggests that a real quill was used because it was so easy to replace if stolen, and for a number of years it was replaced on the Birthday, the tradition stopping when it became difficult to source suitable feathers. If you’re interested in the history, the Museum of Writing has a blog which features a video on A Short History of the Quill, showing how a quill pen was made.

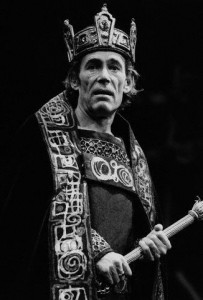

Val Horsler’s explanation of why the tradition began is certainly plausible, but I wonder if those mending the monument in the 1860s might also have got the idea from another monument that was created around 1605 in London, to John Stow. This is in the churchof St Andrew Undershaft in the City. John Stow, often referred to as the Father of London History, published The Survey of London in 1598. For many years a memorial service to Stow was held annually by the Merchant Taylors Company of which he was a member, at which the quill he holds was replaced. Nowadays the service takes place every three years and it’s attended by a group of London Historians. As you can see from the photograph the monument is easy to reach: the person replacing the quill appears to stand on a single wooden step.

Stow’s monument, showing him, quill in hand as he writes in a book, is notably similar to Shakespeare’s and, being only a few years old, could have been chosen as a model when Shakespeare’s monument was designed. It’s to be hoped that the charming custom of replacing the quill as part of the annual Birthday celebrations will continue, even if doing so requires the use of a ladder.